Is the European Parliament Missing its Constitutional Moment?

Over the years, step by step, the European Parliament has won a share of real constitutional power. At times, as in 1984 with the Spinelli Draft Treaty and in 2002-03 in the Convention on the Future of Europe, Parliament has had a decisive influence on the constitutive development of the European Union. At other times, MEPs have found it just as difficult as the European Council has done to make constitutional sense of a Union which is an uneasy compromise between federal and confederal elements. If EU governance is congenitally weak it may be because its institutions are unable to manage the dichotomy between supranational and intergovernmental. Today, circumstances have thrown the European Parliament a golden opportunity to take a major step in the federal direction – but it looks as though MEPs are going to retreat again.

As long ago as 1951, the Treaty of Paris gave the nascent European Parliament the job of drawing up proposals for election by direct universal suffrage in accordance with a uniform procedure. After much grunting and groaning, the first elections were held in 1979. But the electoral procedure was not uniform. A degree of uniformity was introduced in 1999 when, thanks to Tony Blair, all fifteen states held elections according to one or other system of proportional representation. But the elections still remain more national than European: the candidates are selected by national political parties, campaign on national platforms on mainly national issues, and are elected according to different (albeit proportional) national procedures. Although confederations of national political parties have been created at EU level, these organisations are not real political parties: they have next to no influence on the outcome of the European elections; they are actually prohibited from campaigning directly inside member states; and their relationship with the party political groups in the Parliament remains casual and tenuous. Undeceived by these Potemkin type European parties, the media continue to focus on national politics and do a disservice to any citizen elector wishing to vote on European issues.

Seat apportionment

The Treaty of Lisbon changed the designation of MEPs from being representative of “the peoples of the States brought together in the Community” into being “representatives of the Union’s citizens”. Lisbon maintained Parliament’s right to initiate a uniform electoral procedure (Article 223(1) TFEU). But it also vested the Parliament with a new power to propose the reapportionment of seats in the House to reflect demographic change as well as to cater for the accession or secession of member states (Article 14(2) TEU). The divvying up of parliamentary seats between states had always been subject to unseemly bartering, usually in the early hours of the morning at the close of some fractious intergovernmental conference called to amend the treaties. Several in the European Council at Lisbon knew they were gifting the Parliament a poisoned chalice – especially as the treaty added the rejoinder that the “representation of citizens shall be degressively proportional” with a minimum of six seats per state and a maximum of 96.

Needless to say, the actual apportionment of seats in the Parliament has never yet met the criterion of the federalist principle of degressive proportionality. The present composition of the Parliament elected in 2014 is in serious breach of the treaty. Degressive proportionality means that MEPs from larger states should represent more people than MEPs from smaller states, and, conversely, that more populous states should have more MEPs than less populous ones. As things stand today, however, French, British and Spanish MEPs represent more folk than German MEPs; Dutch MEPs represent more than Romanian; Swedish and Austrians more than Hungarian; Danes more than Bulgarian; and Irish more than Slovak.

After a bruising row about the number of seats to be afforded Croatia when it joined up in 2013, the European Council took a decision, in accordance with Parliament’s requests and with its consent, to try to reach agreement on “establishing a system which in future will make it possible, before each fresh election to the European Parliament, to allocate the seats between Member States in an objective, fair, durable and transparent way”. In order to have the formula operative in time for the 2019 elections, Parliament was asked to come up with proposals before the end of 2016 – a target which it signally failed to meet. Opposition from middling-sized states, currently over-represented, stymied progress. This is a pity, and fails to exploit the fruits of an earlier enquiry conducted by leading mathematicians at the behest of the Parliament in which a viable approach was presented.

Transnational lists

Parallel to the debate about seat apportionment, support has been growing for the federalist proposal that a certain number of MEPs be elected for a pan-European constituency from transnational party lists. The purpose is to breathe life into the European dimension of electoral politics and thereby strengthen the democratic legitimacy of the Parliament. The reform would pitch the EU-level parties into competition with each other for ideas, votes and seats. MEPs elected from the transnational list would be accountable to these federal political parties, which would themselves be regulated by EU law and subject to the surveillance of an EU-level electoral authority. The law would stipulate that a minimum number of different nationalities should appear on each transnational list: but in any case the parties would be looking to field a diverse range of candidates.

The introduction of the transnational element would electrify the European Parliamentary election campaigns and stimulate increased turnout. It would satisfy the treaty objective of a uniform electoral procedure and give practical expression to the concept of an MEP as representative of all EU citizens. It would give each citizen a second vote in the election, additional to his or her traditional vote for candidates standing in national or regional constituencies: a tangible manifestation of EU citizenship. The installation of transnational lists would give real meaning and direction to the role of Spitzenkandidaten, controversially introduced by partial experiment in 2014, whereby the EU parties select champions for the campaign.

Although the European Parliament has backed the concept of transnational lists in theory, in practice its steps towards their introduction have been faltering. Electoral reform is always difficult, of course, because serving parliamentarians risk losing their seats. Moreover, conservative forces in the current Parliament are stronger than the progressive, and the rise of the nationalists seems to have intimidated the federalists. But in June 2014 the European Council committed itself to revisiting the method of choosing the next Commission President, as the treaty enjoins, “taking into account the elections to the European Parliament and after having held the appropriate consultations” (Article 17(7) TEU). A decent proposal for transnational lists headed by Spitzenkandidaten would settle the matter satisfactorily. Fully worked-out proposals to adjust the statute governing elections to the Parliament have been published already.

Brexit

One of the more interesting aspects of Brexit is to consider what can be achieved by the EU without the British that it has not been able to achieve with the British. Electoral reform is a very good example. British ministers in the Council were without exception opposed to the federalist concept of transnational lists, as was a very large majority of British MEPs. The departure of the UK will not only remove these political obstacles but will also leave vacant 73 seats in the next Parliament. Those empty seats can be put to good use.

Seizing the initiative, Emmanuel Macron, true to his manifesto, has taken up the proposal for a transnational European constituency at the level of the European Council. The Italian government, with its long-serving Minister of Europe Sandro Gozi, launched the matter in the first place. The Belgian and Spanish governments are also in favour. Martin Schulz for the SPD, along with the German Liberals and Greens, back the plan. In the Parliament, the federalist cause is led by the Liberal leader (and Brexit coordinator) Guy Verhofstadt. He won a vote in November 2015 to include a reference to a “joint constituency” in the Parliament’s most recent report on electoral reform (which otherwise merely tinkered annoyingly on the edges of the problem). But now, just at this moment when the time appears to be ripe for radical change, MEPs are in danger of losing the plot.

The most recent draft report on the matter from the Constitutional Affairs Committee appears not to accept that the UK is leaving the European Union before the next elections in May 2019. The co-rapporteurs, Danuta Hübner (EPP) and Pedro Silva Pereira (S&D), use the excuse of uncertainty surrounding Brexit to put off until 2024 the two critical decisions about the formula for seat apportionment and the introduction of transnational lists. Instead, they would merely use 51 of the UK’s 73 vacant seats to reduce (but not eliminate) the abuse of the principle of degressive proportionality. This adjustment to the distribution of seats among member states would take place at some unspecified date after the actual 2019 election once Brussels had noticed that the Brits had gone.

The rapporteurs, furthermore, attempt to muddle the argument over the composition of the Parliament by raising the question of voting weights in the Council. The issue of balance between the two chambers of the bicameral legislature is indeed something that needs to be raised at the next Convention which will be called to revise the Treaty of Lisbon once the British have well and truly left. But nobody has asked MEPs to raise that matter now, for which there is no legal necessity. And if MEPs cannot make progress on reforming their own internal affairs they are scarcely eligible to interfere in the internal affairs of the Council. Such prevarication – “the time is not ripe” – and the lazy thinking behind the draft AFCO report amounts to a political fix that, were it to be adopted in its present form, would put the Parliament in disrepute – and even at risk of being found by the European Court of Justice of having failed to act correctly.

The package deal

Depressingly, the initial reception of the draft report (11 September) gives little hope that the committee will amend it appropriately. Too few members manifested an acquaintance with mathematics, political science or constitutional law. Even the opinion of the Parliament’s legal service was ignored, which says that MEPs can go ahead and take the decision on seat apportionment before the Article 50 talks confirm the UK’s exact departure date.

It is now up to the political leadership of the Parliament to realise that the British people will not elect new MEPs in 2019, and to draw appropriate consequences for the House. Even in the event that there is a slight delay on Brexit in order to polish or translate the text of an Article 50 secession treaty, the UK government will simply fail to organise polling for the new European Parliament. The UK may indeed be in breach of EU law for having failed to hold an election, but by that stage we will all be beyond caring. And elections can be held and a new Parliament assemble unimpeded by the retirement of the Brits.

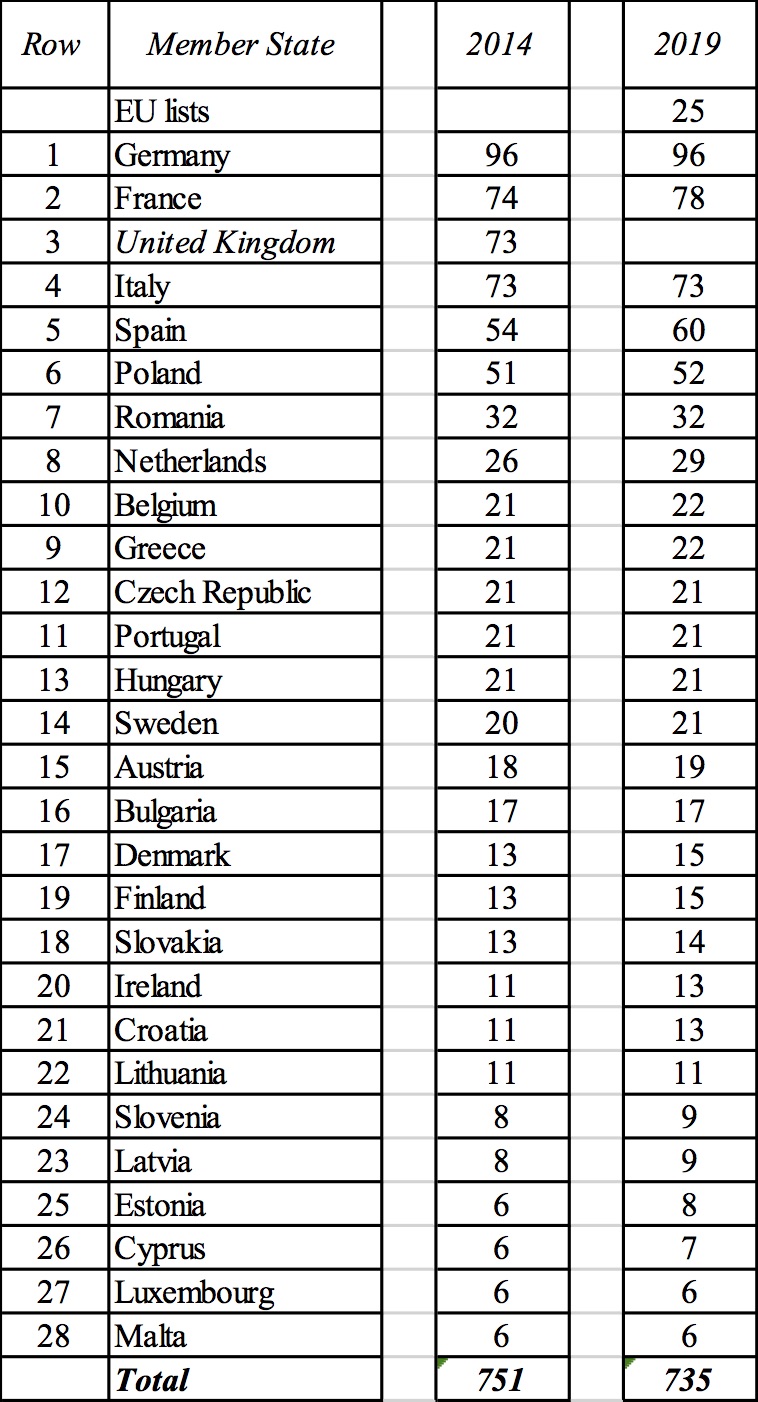

As President Macron has identified, the fact is that the 73 ex-British seats give the Union both the perfect chance and ample scope not only to introduce the arithmetical formula but also to install a transnational list of, say, 25 MEPs, as well as reducing the overall size of the House to save money. The table below shows how this might be done – and all without the loss of a single MEP to any state.

The European Parliament should be pushing forward on all these three fronts. MEPs must maintain their earlier decision to back the pan-European constituency, and neither they nor the Council can dodge their legal obligation to reapportion seats in advance of the 2019 elections. The European Council and Parliament working together can act constructively to consolidate the Spitzenkandidat exercise.

In the end, all these reforms need consensus in the Council as well as the consent of MEPs, but starting off the process is the job of Parliament. Although few MEPs know it, they hold the cards in their hands. To fail to start negotiations with the Council on this available democratic package will expose a lack of political seriousness on the part of the European Parliament, in fact an abnegation of its constitutional duty. United Europe will never be built on the basis of the self-interest of the in-crowd, by procrastination and dissembling. Europe badly needs a parliament that seizes an opportunity to make a democratic advance and turns it into a constitutional moment.

TABLE:

The table shows how, post-Brexit, a transnational list of 25 MEPs could be introduced in 2019 along with the introduction of the arithmetical formula (Base + Power Compromise model (using 0,8 as the power). The overall size of the House is reduced from 751 to 735. No state (other than the UK) loses seats. Degressive proportionality is respected.

Helfen Sie, die Verfassung zu schützen!

Die Verfassung gerät immer mehr unter Druck. Um sie schützen zu können, brauchen wir Wissen. Dieses Wissen machen wir zugänglich. Open Access.

Wir veröffentlichen aktuelle Analysen und Kommentare. Wir stoßen Debatten an. Wir klären auf über Gefahren für die Verfassung und wie sie abgewehrt werden können. In Thüringen. Im Bund. In Europa. In der Welt.

Dafür brauchen wir Ihre Unterstützung!

In any case the current pratice is discriminatory against citizens of larger states. The votes of citizens have different weights. And the reforms as you demonstrated even aggravate the discrimination by disproportion.

Do you believe the transnational lists would really increase the democratic nature of Europe? Without a single language, this component of the election would just be a series of proxy battles in national media between national political figures. Pro-Europeans would be the Merkel list, a far-left group would be the Mélénchon list, etc. If there were demand for a pan-European party, someone would have already filled the role.