Brexit and the Argentinisation of British citizenship: Taking care not to overstay your 90 days in Rome, Amsterdam or Paris

This is an updated version of the article “Brexit and Citizenship” written before the referendum.

What are the likely consequences of Brexit for the status and rights of British citizenship? Is it possible to mitigate the overwhelming negative consequences of the UK’s withdrawal from the EU on the plane of the rights enjoyed by the citizens of the UK? The Brexit referendum result will most likely mark one of the most radical losses in the value of a particular nationality in recent history, also standing out as a most remarkable vote favouring the dramatic reduction of rights enjoyed by all without, at the same time, outlining any clear problem that such a downgrade would seek to solve.

A glance at the EU Treaty makes clear that EU citizenship as such cannot possibly affect, legally speaking at least, the regulation of withdrawals from the Union: Article 50 TEU, which establishes the procedure to be followed by any withdrawing state, does not contain any EU citizenship-related conditions. Imposing such on a people of a Member State that has just voted precisely to leave the Union would be nothing but a direct attack on the letter and purpose of the provision making withdrawals possible.

This being said, we have to realize that from the day when the UK withdraws, UK nationals are by definition not EU citizens any more: the Treaties are quite clear about the fact that this legal status is based on the nationalities of the Member States (Art. 9 TEU). Once the UK is not a Member State, its nationality cannot possibly trigger EU citizenship status. This means that UK citizens in the EU will have a default legal position inferior to Russians and Moroccans (whose countries have non-discrimination clauses in the agreements with the EU), besides losing all the well-known perks of EU citizenship ranging from free movement in the EU, including the right to work and to settle anywhere in the Union without any prior authorizations and non-discrimination on the basis of nationality, to political rights at local and EP level in the country of residence, and consular protection abroad via the representations of other Member States of the EU (Part II Treaty on the Functioning of the EU).

Especially the loss of free movement and political rights will hurt. Once free movement is lost, UK nationals will only be able to work and reside in their country (including the Channel Islands, Gibraltar and the Island of Man, of course), not all over the continent. This is a cap on aspirations and possibilities: full sovereignty comes with its territory. Once political rights at the European level are lost, the citizens of the UK will not be able to influence the development of European law, which will remain overwhelmingly important in the UK, as the Channel is unlikely to become a sea and the old trading ties will remain. Full sovereignty is only possible in the world of Realpolitik: as a junior partner the UK is bound to be a constant recipient of rules in a one-way relationship. The loss of political rights at the municipal level for all the UK citizens residing in the EU will mean that Britons in Spain, France and Italy will not have a say at all in local politics, even in the municipalities where their interests are considerable, turned from equal members of the local communities into mere guests. Foreigners are outsiders.

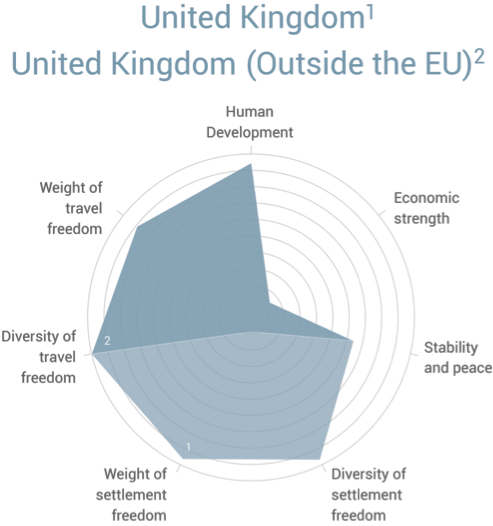

Currently, but not for long, still belonging to the elite club of the top-quality nationalities in the world, UK citizenship’s position, like the Pound following the Brexit vote, could soon be in a free fall. Applying the methodology of the Quality of Nationality Index which I designed together with Henley & Partners to the Brexit situation demonstrates a most likely loss of at least 30% of UK nationality’s value – an overwhelming downgrade to the level of Argentinean and Chilean nationality (figure 1). This is a more dramatic loss of value than what war-ridden Ukraine and protest-shaken Bahrain have experienced over the last years.

Figure 1 (methodology source: Henley & Partners–Kochenov Quality of Nationality Index, 1st ed., Zürich: Ideos, 2016)

This situation is unquestionably bound to have political implications, necessarily affecting the negotiators in charge of the Brexit agreement with the EU. It seems it would be too cynical of them to assume that agreeing to endow UK citizens residing (or, importantly, wishing in the future to reside) in the other Member States with a status inferior to that of some other third-country nationals would be acceptable, even if this seems to have all along been the position of the British government (as testified by the decision to hold the referendum in the first place) and the British courts. Absurd as it may sound, Paris, Rome, Amsterdam and Berlin can actually end up being off limits for those UK citizens who would like to overstay the 90 days of visa-free stay for foreigners the Schengen system permits. Non-EU citizens are foreigners.

It is unquestionable that reducing the scale of rights is bound to derail plenty of lives. Consequently, EU citizenship rights are bound to play an important role politically in the context of the withdrawal negotiations. The comparison between the loss of rights experienced by the citizens of the UK on the one hand and other Europeans on the other (so long as free movement and other EU-level rights will seize being provided in the territory of the UK) could sound unjustified in terms of the sheer difference in scale between the two groups facing the inevitable reduction of rights (only the UK in the case of the Frenchmen and Estonians and all the rest of the EU in the case of post-Brexit UK citizens). Yet, from a purely pragmatic point of view such mutual downgrade is good news, since when both parties are threatened with a loss, a more productive dialogue could be said to be more likely. This increases the hope for an acceptable negotiated solution.

The question is whether a dramatic loss of rights by the citizens on both sides of the newly-emerging EU border is an inevitable follow-up of a withdrawal of a Member State from the Union. Could some solution to be found to avoid it?

Any arrangement granting quasi-citizenship of the EU to the citizens of the post-Brexit UK will de facto result in affecting negatively the core considerations behind wanting to withdraw – however arcane and esoteric these can seem to a minimally informed observer – thus openly playing against the political objective of leaving the Union supported by 51.9% of voters so clearly. The resulting political balance here can be very tricky: how much can real and tangible rights of UK citizens be cut in the name of the blurred and unclear rhetoric behind the case for withdrawal boasting no clear programme, which actually won? This balance will be for the same elites, who allowed for the referendum in the first place to try to execute, keeping in mind that maintaining an EEA-like arrangement with the EU in the context of the free-movement of persons – i.e. winning a right to overstay 90 days in the Schengen zone without a risk of being deported and barred from Europe for several years – will obviously have a very high price at the negotiating table with the EU aware of possible domino-effect of any withdrawal. This price will necessarily include at least reciprocal arrangements for EU citizens in the UK. Negotiating with the remaining Member States collectively makes it impossible for the UK to discriminate between the nationals of the remaining EU Member States. This means that all the EU citizens in the UK will most likely stay where they are, enjoying a very similar – if not the same – level of protections.

Bilateral negotiations following Brexit could provide an alternative possibility, implying the introduction of full reciprocal free-movement arrangements bilaterally only with those EU Member States where the majority of the UK expats reside, plus, perhaps, the most economically successful states, thus dropping all but a handful of the Member States, arguing that these are anyway of little interest for UK citizens in terms of settlement and work opportunities. This approach is bound to be put on the table in any bilateral setting, given the relative mono-dimensionality of the flows of free movement of labour in the EU. It is not that UK citizens are all packing up to go to Slovakia or Bulgaria. The contrary is true. Dropping much of Eastern and some of Southern EU from the free movement arrangements could thus be presented by the negotiators as a reasonable way forward, to strike the right balance between the political goal of withdrawal and the need to make sure that own citizens of the seceding state do not suffer a really serious blow to their rights. The consequences for countless individuals and for the idea of European unity, should such an approach be chosen, could be drastic indeed, a valid reason to prefer a strictly multilateral approach and a built-in legal guarantees in the final arrangement, against any such bilateral moves in the future. The EU is obviously expected to make any bilateral deals of this kind impossible and to make sure that the principle of non-discrimination on the basis of nationality among EU citizens of any origin is adhered to in full, including in the context of the UK’s new relationship with the internal market. Selective bilateral approaches will not work.

In the grand scale of things, the huge losses in terms of rights and the quality of nationality which the citizens of the UK are bound to experience now that they have spoken is but a cherry on top of the Brexit pie, the recipe of which is so difficult for any intellectually honest person to understand. That the consequences of withdrawal will be harmful for many without solving any non-existent problem at hand, like welfare tourism for instance, is as clear as day. Britain awoke to a new, much less rational world of inexplicable mysticism and the self-inflicted Argentinization of its citizenship.

For the full story, please consult my LSE ‘Europe in Question’ paper written before the vote.

Helfen Sie, die Verfassung zu schützen!

Die Verfassung gerät immer mehr unter Druck. Um sie schützen zu können, brauchen wir Wissen. Dieses Wissen machen wir zugänglich. Open Access.

Wir veröffentlichen aktuelle Analysen und Kommentare. Wir stoßen Debatten an. Wir klären auf über Gefahren für die Verfassung und wie sie abgewehrt werden können. In Thüringen. Im Bund. In Europa. In der Welt.

Dafür brauchen wir Ihre Unterstützung!

Does the author believe that the alleged “huge loss in terms of rights and the quality of nationality” will be felt by the denizens in the UK equally? Or is he engaging in a dialogue about the privileges and interests of the elites? Is his contribution a symptom of and an example for the a-synchronicity in the “Weltsicht” of elites and normal citizens, which might be at the heart of the outcome of the referendum?

Any special reason why “argentinisation” was used Britons will be put in a position similar to that of many other countries and not just Argentina?

And actually, many Argentine citizens are also EU passport holders or could be elegible for EU citizenship, most notably Italian citizenship, although there are also Spanish, Polish, maybe even Portuguese and Irish dual citizens. So some Argentines will be in a better position than Britons.

Britons will be similar to Argentines in the sense that (at least some of them) will do anything in their power to obtain dual citizenship.

In response to the previous comment, the effect of loss of citizenship does not only affect the elites but any working or middle class person who wishes to live and work within the Union with no visa restrictions, as well as study for cheap or even no tuition for EU students in countries like Sweden, Netherlands, Italy, Spain.

As an Australian I can imagine a future jingoistic UK from which many Remainers will want to flee. They will seek refuge almost anywhere.There may not be any Pacific islands left to flee to; the Middle East and Africa may serve, but these governments could turn back the British boats and,for good measure,detain the fleeing Brits in offshore prison camps, thus punishing the equivalent of the educated and critical citizens who are at present fleeing hellholes like Syria and Iran.