Germany’s Domestic „Königstein Quota System“ and EU asylum policy

The tragic death of more than 300 refugees off the coast of Lampedusa has ignited a discussion on different aspects of the current asylum policy in Europe. Points of contention include the role of the European borders’ agency Frontex, living conditions of asylum seekers, economic development of countries of origin as well as the fight against human trafficking. There is another critical facet to the discussion: EU Member States complain about distribution of asylum seekers within the EU; Italy and Germany, in particular, have accused each other recently of insufficient action. Martin Schulz, EP President, prominently called for more solidarity among EU Member States.

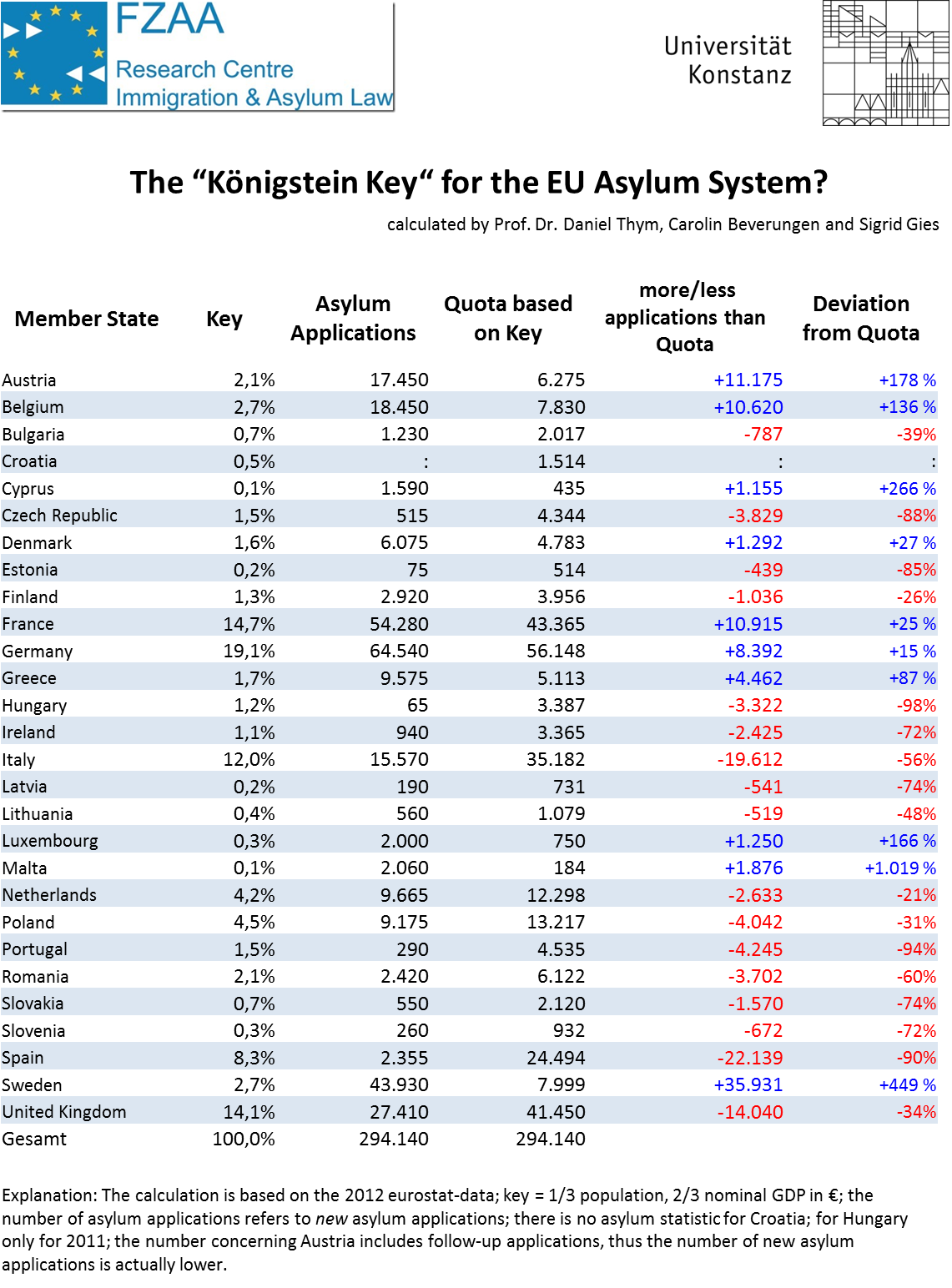

This discussion has prompted us to ask what the situation in Europe would look like if – hypothetically – the same distribution quota system applied within Europe, which Germany has exercised for more than twenty years to distribute migrants among its federal entities, the Länder. Within Germany, a quota is calculated in relation to each Land which combines total tax revenues and population numbers (“Königstein Quota System”). The underlying idea is that poorer Länder should not bear the same burden as equally populous, but comparatively richer Länder. This method was developed in 1949 in order to administer the financing of common projects, such as research funding, by all Länder, and was later applied to asylum procedures. Within Germany, 64.540 people who applied for asylum last year, were distributed among the Länder in accordance with the Königstein quota.

Our calculation model

The Königstein Quota System is constituted of a weighted addition of population (1/3) and tax revenue (2/3). Certainly, one could argue endlessly about the suitability of this exact formula, but one cannot deny a sense of intuitive plausibility in combining population numbers and financial power. By all means, this key takes one step towards a distribution mechanism which gradually adjusts the obligations of the different Länder to their financial capabilities. What would this mean for the European Union?

When applying the quota system to the EU, one must modify the calculation, since there are no reliable data on tax revenues. Instead, we use the Gross Domestic Product (similar to the EU itself, which defines the national share of EU budget contributions on the basis of GDP), which counts for two thirds of the quota. In fact, we apply the nominal GDP (as opposed to the real or constant GDP which is adjusted according to purchasing power) which is more favorable for poorer countries. On this basis, our Königstein Quota model defines a quota for each country: For example, the population of Germany accounts for 16.1 % of the total population of the EU but generates 20.6 % of its GDP, resulting in a German quota of 19.1 %. For poorer Romania, on the other hand, the quota is 2.1 % even though it accounts for 4.2 % of the overall population. In a second step we put the country-specific distribution key in relation to the total amount of asylum applications in 2012, which reveals the “proportionate” share of each country.

Our calculation is based on official Eurostat-data, although we are aware that the actual situation is different in some countries. Especially in south and east European countries with weak asylum systems, low welfare benefits and unattractive reception conditions, fewer of the migrants present in the country apply for asylum than in Belgium or Sweden. Instead, more migrants live clandestinely in Southern and Eastern Europe (or move within the Schengen area from Lampedusa to Hamburg). This difference is also reflected in recent protests that featured prominently in the news: while in Germany asylum seekers and so-called “tolerated” migrants (whose deportation has been suspended for the time being) who receive reduced welfare benefits protest against the German asylum system, ‘clandestinos’ receive frequent publicity in Italy and Spain. The latter do not feature in the Eurostat-statistics – yet we use them for lack of better options.

The result shows that the European asylum system is indeed characterized by a lack of inter-state solidarity. There are grave differences among Member States – and the distribution of asylum seekers is indeed surprising. It is not only the border states in the south and east of the EU which carry the main burden, but also countries like Belgium or Sweden, which are far off the shores of Lampedusa. Countries like Malta and Cyprus are surely overburdened, but on the other hand most southern European states like Italy and Spain receive relatively few asylum applications (all details are available as pdf).

Consequences for legal policy

The reason for our calculation was primarily curiosity. What is the result, if one applies the German system to the EU? Discussions on solidarity among member states are en vogue, but most reproaches and demands remain abstract. Ideally, our calculation can contribute to a more profound discussion on causes, connection and solution of problems within the European asylum system. Obviously the problems, which NGOs identify mainly in asylum systems in Italy, Hungary and Poland, do not only stem from geographical location and allegedly high numbers of asylum applications. Based on their size and financial capabilities, these countries are in fact not overburdened according to our calculation. The problem seems to be much more complex than that. What seems to be missing in some countries is the willingness to establish an efficient and reliable asylum system. It is not without reason that the EU-Commission recently filed legal action against Italy for deficits in its asylum system.

At the same time, our calculation shows that the much debated Dublin-System, which allocates responsibility for asylum seekers to the different EU member states by allowing the transfer of asylum seekers to another EU member state under certain conditions, can at best be a starting point for the genuine distribution of responsibility. Comparing statistics for Germany and the results of our model, one can see that the Dublin system may alleviate asymmetrical distributions (as is the case for Italy), but at times may also support them (as is the case for Belgium and Malta). Therefore, numbers alone do not allow for a proper evaluation of the Dublin-System. At best, numbers show that Europe needs complementary or alternative methods for the distribution of responsibilities.

What deserves support according to our opinion is the EU asylum office EASO, located in Malta, which trains national administrative officers and furthers Europe-wide cooperation aimed at creating conform stipulations for the recognition of refugee status. We also welcome the adoption of new EU directives which contain more detailed rules for the asylum procedures and reception conditions. These measures support asylum systems throughout the European Union in identifying persons entitled to protection swiftly and reliably as demanded by EU norms. Without this reliability, a Common European Asylum System, which the EU Treaties aspire, cannot function in the long run. If this can be achieved, new forms of solidarity and distribution of responsibility could be set up or reinforced step by step. Such a system would surely be more complex than our model based on quotas, which ignores humanitarian aspects or family union. Our intention is not to propose a specific design; our calculation only aims at instigating further debate.

We would welcome such debate. We are united in the conviction that the times where every state protected refugees by itself without cooperating with its neighbors or asking for the root causes of flight are over. Effective protection of refugees, ranging from countering causes of flight, effective and efficient procedures to durable solutions, has to be addressed by the states collectively. Social sciences teach us that collective action is often aggravated by the tragedy of the commons, if everyone aims for his own benefit. If this is correct, the main benefit of a comparatively rigid distribution of tasks, such as the Königstein Quota System, would be to turn Member states from rivals into partners. Mutual accusations would give way to the cooperative search for adequate procedures and best solutions.

Helfen Sie, die Verfassung zu schützen!

Die Verfassung gerät immer mehr unter Druck. Um sie schützen zu können, brauchen wir Wissen. Dieses Wissen machen wir zugänglich. Open Access.

Wir veröffentlichen aktuelle Analysen und Kommentare. Wir stoßen Debatten an. Wir klären auf über Gefahren für die Verfassung und wie sie abgewehrt werden können. In Thüringen. Im Bund. In Europa. In der Welt.

Dafür brauchen wir Ihre Unterstützung!