How Political Turmoil is Changing European Constitutional Law: Evidence from the Verfassungsblog

As millions of Europeans have gone into either voluntary or government-imposed lockdown amid fears that the Covid 19 outbreak might turn into the worst public health disaster in living memory, Europe is experiencing its umpteenth economic and political upheaval in the span of little more than a decade. It is as if one crisis had ended only for the next one to pop its head out: a financial meltdown, then a sovereign debt crisis, mass unemployment, a refugee crisis, a populist surge, Brexit, democratic backsliding in Poland and Hungary, rising Euroscepticism. For a constitutional law scholar, the contrast with pre-crisis Europe could hardly be sharper. In retrospect, Europe, and much of the world, seemed then to be enjoying a golden age of stability – to borrow Stefan Zweig’s nostalgia-filled, yet percipient description of the European societies swept away by the Great War. Constitutional courts had been spreading all over the continent while the European Court of Human Right and the Court of Justice of the European Union were growing ever more powerful. Centre-left and centre-right parties alternated in power at regular intervals. Economic slowdowns were comparatively mild. The rule of law looked triumphant. Democracy was unchallenged. The authority of judges appeared unassailable while human rights were confidently ascending to the status of secular religion.

The discipline of constitutional law – which we take here to include EU constitutional law – reflected this prevailing state of stability. Whether in France, Germany, Spain or Italy, or in the new democracies of Central and Eastern Europe that had or were on the verge to join the European Union, constitutional law scholarship largely consisted of elaborations or reconstructions of constitutional court opinions. Whether Karlsruhe, Strasbourg or Luxembourg, courts, not scholars, were setting the agenda. In Germany, Bernhard Schlink characterized this state of affairs as “constitutional court positivism” (Verfassungsgerichtspositivismus). In the EU law context, Hans Micklitz and Rob van Gestel described it as “case law journalism”. With constitutional judges, whose power and authority could be taken for granted, firmly in the driving seat, European constitutional scholarship often an exercise in case law compilation, interspersed with occasional praise or disagreement for the course of action chosen in a particular case.

“Law vs Politics” is artificial as shockwaves show

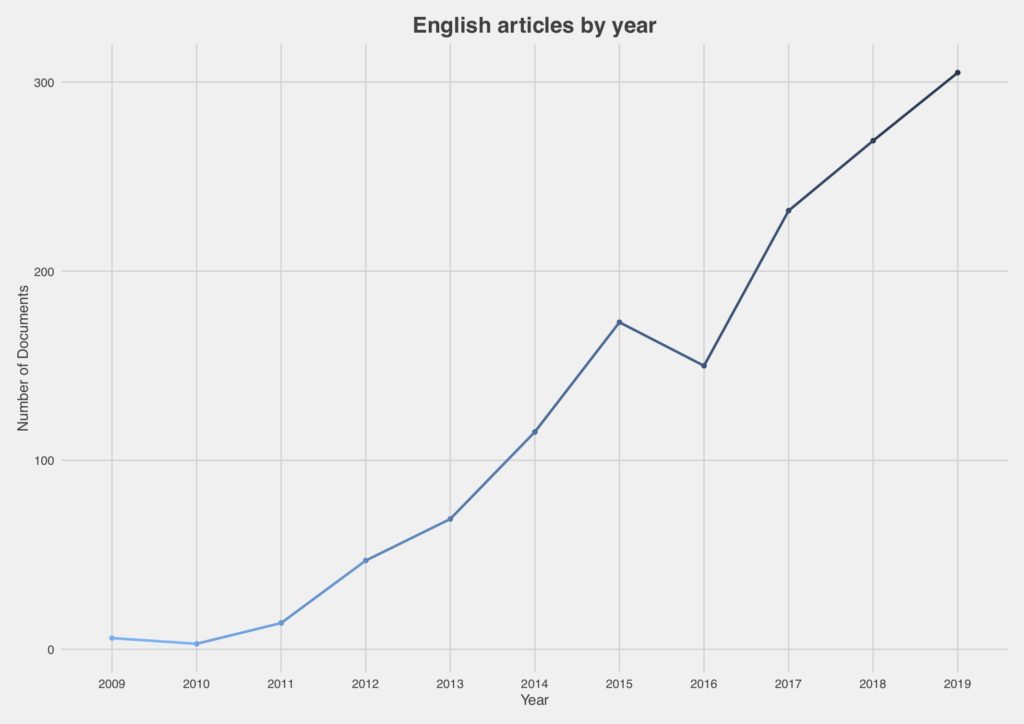

The repeated shocks and looming threats now confronting European societies together with the supranational institutions they erected in the wake of the Second World War may be changing this. Much of what could be taken for granted when politics was dull and predictable – whether it is the authority of constitutional tribunals, the independence of the judiciary or support of democratic-liberal values – can no longer be assumed. Constitutional law, therefore, can no longer be treated as if it were independent and insulated from politics. It never was. But the shockwaves that have rippled through the European political order have exposed the artificial character of the law vs politics distinction, forcing constitutional law scholars to adapt. Contributions to the Verfassungsblog provide evidence for this evolution. The Verfassungsblog publishes posts on constitutional developments in Germany and Europe (and occasionally beyond) since 2009. Initially most posts were in German, but English language contributions have increased considerably over time to more than 300 in 2019 (see Chart). To check our hypothesis that contributors have been paying increasing attention to politics, elections, parties and the electoral cycle, we used computer scripts to harvest the texts of all the posts that have appeared on the blog since 2009 and up to 2019.

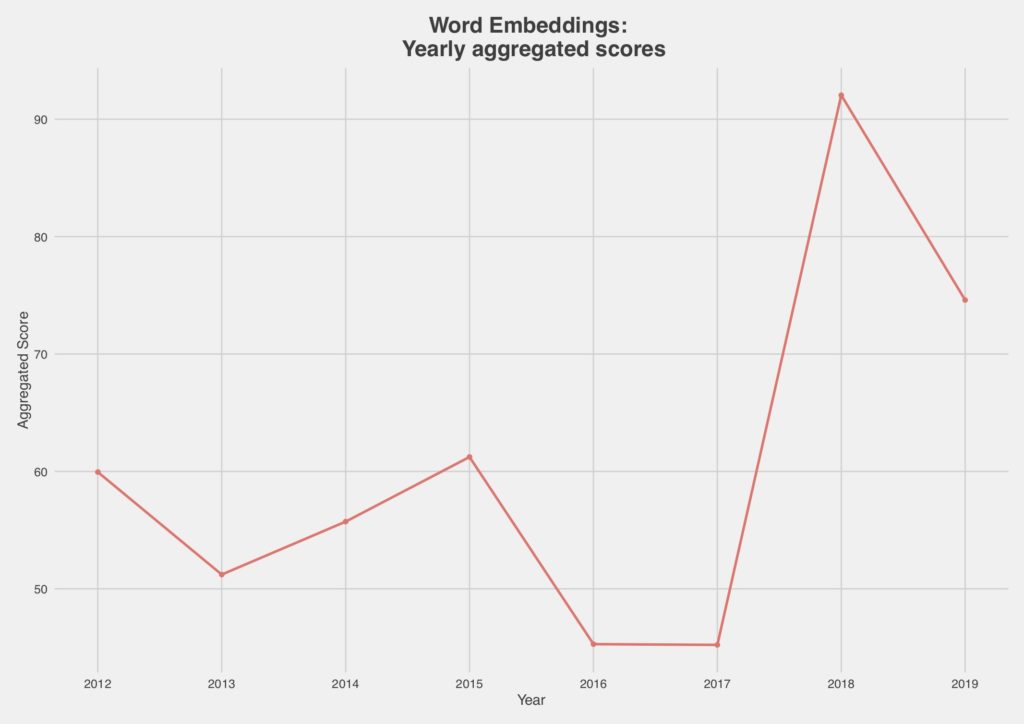

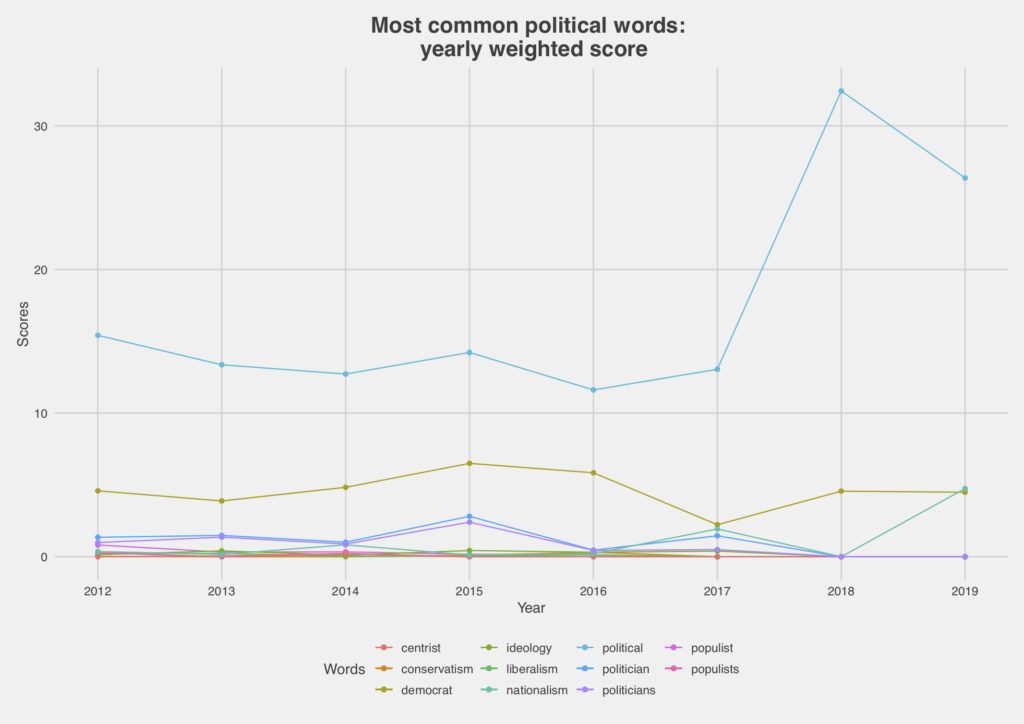

We then applied a technique called “word embeddings” to retrieve concepts associated with politics in these blogposts. Word embeddings is based on principles from distributional linguistics. The basic intuition underpinning distributional linguistics is that words with similar meaning tend to appear in similar contexts – the meaning of a word is defined by the company it keeps. A machine learning algorithm (neural network) is then trained to learn the context associated with each word in the corpus. As with machine learning methods in general, the more data (text) the better. This is why, in addition to training word embeddings with the posts published on the Verfassungsblog, we also used pre-trained embeddings constructed from much larger collections of documents. Google’s pre-trained word embedding model for English, which boasts a vocabulary of three billion words trained on Google News data, and a pre-trained model for German, constructed from Wikipedia pages, with vocabulary of nearly five million words. We used three politics-related words – “politics”, “party” and “populism” in English and “Politik”, “Parteien” and “Populismus” in German – to generate a weighted political lexicon consisting of the words most closely associated with these three words. The lexicon generated by the Google-trained model includes “political”, “conservatism”, “ideology”,”democrat”, “electorate”, “Euroscepticism”. Most of these words also appear in the lexicon generated from the model trained on the English blogsposts, although the latter gives greater weight to “elite” (which relates to “populism”), “society”, “power-holders” and, perhaps unsurprisingly, “constitutionalism”. These associations can be found in the model trained on the German blogposts, too, where “Eliten” appears alongside “Gesellschaft”, “Minderheit” and “Demokratie”.

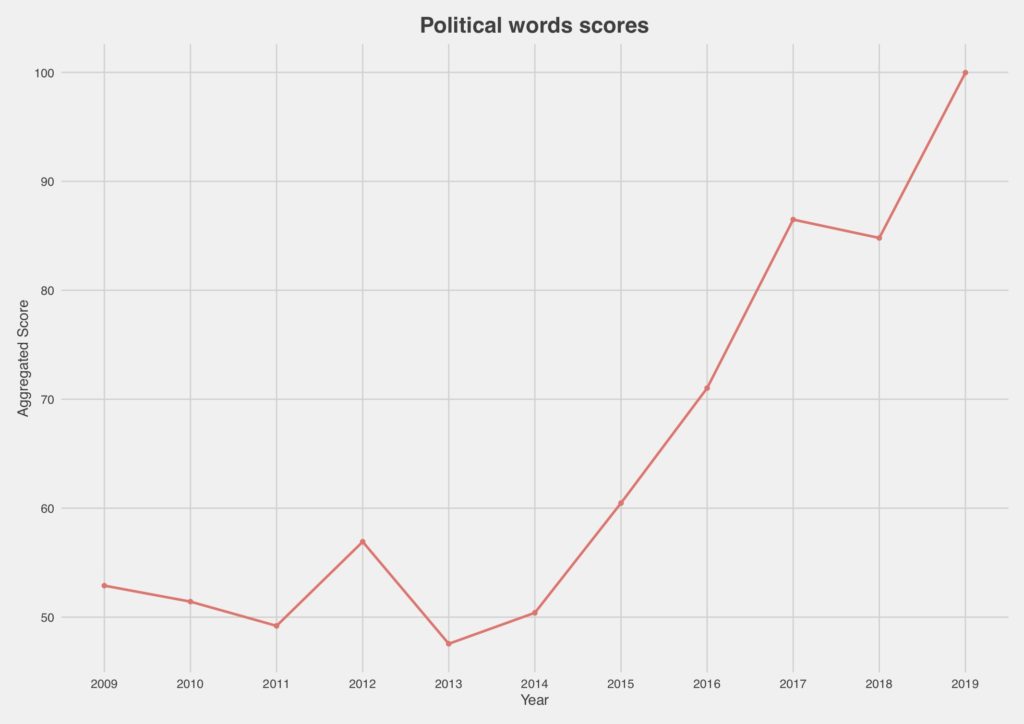

When plotted over time, the relative incidence – that is relative to the number and length of contributions – of terms associated with politics look to have increased significantly over time. This is true of both English and German posts (we excluded contributions in English prior to 2012, as these were too few to give meaningful results). If anything, this evolution seems even more pronounced in the German corpus, possibly because it started from a more “legalistic” baseline. (Note that both charts are based on the pre-trained models.)

We might suspect the word “populism” to be closely tied to the debate triggered by democratic backsliding in Poland and Hungary, which has featured prominently in recent contributions to the blog. However, looking at how the most-recurring political words in our computer-generated lexicons have varied over time in the English contributions, the populist surge doesn’t seem to be driving the growing attention to politics. In fact, among these most-recurring words (remember that our lexicons encompass up 500 terms), only the adjective “political” displays a clear increase in relative use.

Politics is an inescapable variable of European constitutional law

This evolution may not have escaped the attention of long-time readers. Pitting traditional parties against anti-establishment, elite-bashing disrupters, elections have become high-stake, watershed moments of great constitutional saliency, as exemplified by many recent contributions to the Verfassungsblog (see e.g. Giuseppe Martinico’s contribution on Italian politics). Also, contributors have debated the tension between populism and constitutional review while political scientists have engaged legal scholars over the stance of EU institutions towards the Polish and Hungarian governments. The reintegration of politics and the decline of Verfassungsgerichtspositivismus, we believe, are precipitating a broader transformation of constitutional law as a discipline, which, at the same time, represents a return to a more ambitious but, at many levels, equally troubled age. We’re certainly not the first to draw parallels between the crises that have rocketed Europe in the last ten years and the interwar period. Whether it’s a brutal economic recession, the rise of populist demagogues, democratic backsliding and even a global pandemic (the Spanish flu), the resemblances are, indeed, many. Yet the interwar period was also a time of great intellectual effervescence and creativity in constitutional thinking. It saw the great controversy between Hans Kelsen and Carl Schmitt on the merit and design of constitutional review. Kelsen published the first edition of his Pure Theory of Law, which demarcated a research programme in which politics had no place, but he also penned one of the most profound and lucid reflections on the nature and value of democracy. The discipline ignored rigid disciplinary boundaries. Political science, political economy, political sociology and constitutional law scholarship were virtually undistinguishable. Because politics was simply too important to ignore.

Legal scholars usually have their eyes on whatever varies. By contrast, the constants, the parameters that they consciously or unconsciously treat as fixed, they have the tendency to ignore – until these cease to be constants. When politics was boring, the authority of the law, the legitimacy of constitutional courts, the prevailing constitutional settlement, all these were fixed parameters in the dominant intellectual paradigm. They are not anymore. By wiping out old certainties, backlash against judges, attacks on the rule of law, and state of emergency – on top of which we must now add a looming public health disaster – mean that politics can no longer be treated as an implicit, hidden constant. It is now an inescapable variable of European constitutional law, which scholars – starting with Verfassungsblog contributors – are treating as such.

Helfen Sie, die Verfassung zu schützen!

Die Verfassung gerät immer mehr unter Druck. Um sie schützen zu können, brauchen wir Wissen. Dieses Wissen machen wir zugänglich. Open Access.

Wir veröffentlichen aktuelle Analysen und Kommentare. Wir stoßen Debatten an. Wir klären auf über Gefahren für die Verfassung und wie sie abgewehrt werden können. In Thüringen. Im Bund. In Europa. In der Welt.

Dafür brauchen wir Ihre Unterstützung!