Producing Legal History

The European Court of Human Rights’ Lengthy Proceedings

Iustitia dilata est iustitia negata is a famous legal maxim meaning that “justice delayed is justice denied”. It goes without saying that it represents a universal truth. When I was researching on the violations of freedom of expression in Turkey for an article, I realized that this truth was particularly relevant to the European Court of Human Rights (hereinafter “the Court”).

Let me give an example: The Court recently delivered a judgment finding a violation of Article 10 (freedom of expression) in the case Saygılı and Karataş v Turkey (appl. no. 6875/05, 16 January 2018) in which the journalist applicants had been convicted for disclosing the identities of public officials who are involved in the fight against terrorism, thereby rendering such persons targets for terrorist organizations. The judgment of the Court can be seen as an “ordinary” violation judgment at first glance. It may not come as a surprise that the Turkish government did not respect the freedom of expression and the Court drew a line against the government’s authoritarian tendency. But the devil lies in the details. The date of the judgment was 16 January 2018, while the application date of the case was 28 March 2001. That is to say, the judgment was delivered 16 years 9 months 28 days after its application to the Court. If the becoming final process is also considered, the period lengthens to more than 17 years.

This period is nearly a whole career time for some people, especially for many journalists. Moreover, this judgment, which is an example of the “current jurisprudence” of the Court, is examined by law students at Turkish universities, most of whom had not yet came into the world when the victims had applied to the Court. None of the judges at the time of the application are now in office. Erdoğan was not in power then. In fact, his Justice and Development Party (AKP) had not even been founded at that time. The events and backgrounds of the judgment are from the previous century.

As is known, the European Convention on Human Rights was established and ratified by the states of Western Europe against the background of the ruins of World War II and the horrors of Nazism. Also, the Court was founded to protect and enhance the fundamental values of Europe such as human rights, democracy and the rule of law against the possibility of accession to power of a fascist party. Accordingly, the Court is expected to act as a guardian or watchman of human rights in Europe. Nevertheless, the Court looks like a sleeping night watchman sometimes when taking into consideration the above data. This is also against its function and raison d’être.

Let us assume for a moment that the Court existed in May 1933 with this performance. If a journalist who had his books burned in Berlin had applied to the Court in this regard, a judgment declaring a violation of freedom of expression would have been issued in 1950. World War II would have begun and ended, the Holocaust would have happened, the Bonn constitution would have been accepted, all before the Court delivered its judgment.

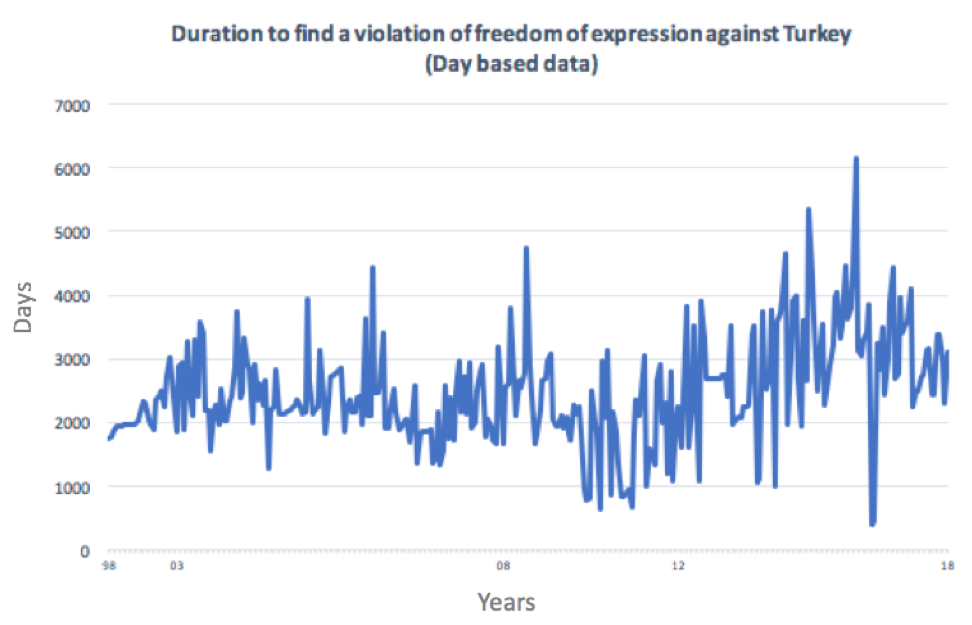

The national socialists were in power for exactly 12 years in Nazi Germany. However, there are many judgments against Turkey regarding violations of freedom of expression, which were rendered in more than this duration. For instance, judgments such as Döner and Others v. Turkey (5,347 days; appl. no. 29994/02, 7 March 2017), Müdür Duman v. Turkey (4,654 days; appl. no. 15450/03, 6 October 2015), Kula v. Turkey (4,439 days; appl. no. 20233/06, 19 June 2018) and Dicle v. Turkey (no.2) (4435 days; appl. no. 46733/99, 11 April 2006) were delivered more than twelve years after their applications.

You may think that these judgments are exceptional and do not reflect the overall performance of the Court. Nevertheless, the average duration of delivering judgments is also not reasonable. There have been 321 violation-judgments against Turkey in the context of freedom of expression between 1998 and 2018. According to my calculation, the average duration for finding a violation of freedom of expression in those judgments is 2,471 days, i.e. six years nine month and eleven days. This number is very high and problematic and the problem cannot be justified with the Court’s workload, since the situation is almost similar with regard to very early judgments of the Court when the workload was lower than it is today. For instance, Incal v. Turkey (9 June 1998, Reports of Judgments and Decisions 1998-IV), in which the Court found a violation of freedom of expression for the first time in 1998, had been rendered four years and nine months after its application. Therefore it can be said that the problem is not new but has been in place for a while.

In fact, below graph, prepared by myself, indicates the times taken to deliver judgments that involve a violation of freedom of expression against Turkey.

These numbers are very high, especially for a human rights court. If a court responsible for guiding human rights such as the right to trial within a reasonable time acts like this, then who guards the guardian?

Long story short, it is obvious that the structure and effectiveness of the Court is doubtful and it should be reviewed. Especially the speediness policy of the Court should be re-revised. Otherwise, it would appear that the case-law of the ECtHR would be a subject of the field of legal history.

Today, a lot of academics, journalists and human rights defenders are hard pressed in Turkey. Some courts in Turkey issued verdicts in several major politically motivated trials against them, based on evidence consisting of writings which do not advocate violence alongside unsupported allegations of connections with terrorist organizations. They want the Court to be a speedy remedy for their unjust victimhood and ask for a voice of justice from Strasbourg. And they are asking how much longer they have to wait and how the lost years of slow progress will be repaired. The Court must fulfil its function. Without further delay.

Helfen Sie, die Verfassung zu schützen!

Die Verfassung gerät immer mehr unter Druck. Um sie schützen zu können, brauchen wir Wissen. Dieses Wissen machen wir zugänglich. Open Access.

Wir veröffentlichen aktuelle Analysen und Kommentare. Wir stoßen Debatten an. Wir klären auf über Gefahren für die Verfassung und wie sie abgewehrt werden können. In Thüringen. Im Bund. In Europa. In der Welt.

Dafür brauchen wir Ihre Unterstützung!