The State of Emergency Virus

The current pandemic is said to be the worst health crisis the world has experienced for a century. Beyond causing thousands to die and millions to lose their jobs, it has also caused more than ever before governments to declare a state of emergency and, thus, to considerably broaden their own competencies. Previous experience, however, has shown that governments do not use their additional powers to save lives but, rather, to make themselves better off. Considering that more than half of the world’s democracies have declared a state of emergency, the rule of law will be subject to a number of dangers in the following months.

Until today, almost 100 countries on all continents have declared a state of emergency. And this is only counting emergencies declared on the national level, implying that federal countries like Australia and Canada could be added to the list, as the authority to declare emergencies in these countries often rests with regions.

A state of emergency regularly implies that the government has the right to derogate from some basic rights – such as the freedom to assemble, to move freely, to practice one’s religion, the right to privacy and so on. And governments are making ample use of their additional powers, just think of the various tracking measures imposed by many governments. A state of emergency also implies that the other two branches of government are weakened. Many constitutions grant the executive the power to rule by decrees, i.e. to bypass the legislature, during an emergency. The judiciary has been weakened in a very hands-on manner during the current wave of emergency declarations: many courts have simply been shut down, implying that it has become difficult or even outright impossible to challenge the legality of government actions. In addition, the Israeli government has challenged the power of the Supreme Court by refusing to follow its directions.

In previous research, we analyzed the effects of states of emergency that were declared following a natural disaster. The current pandemic is a biological disaster but natural disasters also comprise tsunamis, floods, volcano outbreaks and so forth. Our findings were unexpected – and alarming: controlling for the size of a disaster, we find that calling a state of emergency is connected with more – not less – people dying. It thus seems that governments do not use their additional powers to save lives but, rather, to make themselves better off.

Doesn’t sound plausible? But this time is different? Let’s have a look at the facts first. Until today, 98 governments on all continents have declared a state of emergency due to COVID-19. We find that democracies are more likely to declare a state of emergency than autocracies. 33% of all autocracies have declared versus 54% of the world’s democracies, although many autocracies have declared very rapidly. Half of all autocracies declared a state of emergency within a week of the first confirmed case of COVID 19 while democracies typically take twice that time. Both of these findings are immediately plausible: autocrats already enjoy vast powers, declaring a state of emergency will give them fewer extra powers than democratic governments. This is why democracies declare more often. Autocracies are, however, faster in declaring because it is less cumbersome to declare. In academic lingo: fewer veto players need to consent.

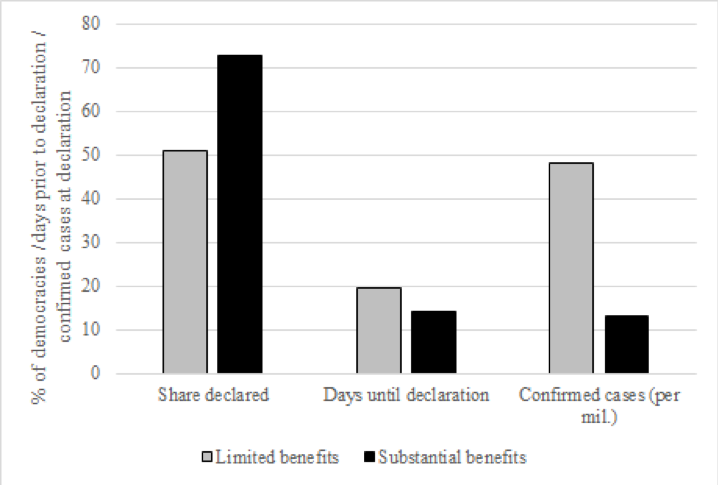

Constitutionalized emergency provisions promise different benefits to governments in different countries: some may dissolve parliament, some may postpone elections, some may suspend individual rights, some may censor the media and so forth. In earlier research, we have created an indicator reflecting these benefits: the right to, for example, dissolve parliament, censor the press and repress civil liberties. A conjecture is that those governments who benefit more from emergency provisions are more likely to invoke them. So can the indicator be used to predict government behavior during the current crisis? Are governments that enjoy more benefits from a state of emergency more likely to declare one? The answer is a resounding yes.

Here are some details, as illustrated in the figure: First, governments that enjoy many benefits from a state of emergency are more likely to declare one than governments that would enjoy only few benefits. This result holds for both democracies and autocracies. Second, governments that enjoy many benefits are faster in declaring a state of emergency. And third, governments that enjoy many benefits declare although on the day of the declaration they have far fewer confirmed cases. In other words, one cannot simply claim that these governments merely declare because they are hit harder. If anything, the data tell the opposite story.

And here are only a number of examples of how politicians have taken advantage of the current states of emergency. Hungary’s parliament has passed a law giving Viktor Orbán the possibility to dissolve parliament and rule by decree for an infinite amount of time. This is close to getting rid of democracy entirely. Pointing at the pandemic and the state of emergency, Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu has sent the country’s courts on vacation, postponing a corruption trial against himself. Sierra Leone did not only declare a state of emergency at a time when not a single person was affected but declared it for no less than an entire year.

A further worry is that the oversight of government authorities often breaks down, and that governments allow authorities a much wider berth during emergencies. During the first two weeks after declaring an emergency, the South African police had for example killed at least eight people when ostensibly enforcing emergency law. In Albania, the prime minister threatened to let the police use similarly violent tactics if citizens do not respect a curfew.

Many more examples from both autocracies and democracies could be offered. But instead, let us point out a number of general dangers that the rule of law will be subject to in the following months. First, governments will attempt to lower the bars for declaring a state of emergency (as Japan, e.g., has already done). This means that we are likely to experience more states of emergency in the future – and more threats to the rule of law and democracy. Second, there used to be a consensus that legislation passed under a state of emergency should only remain valid as long as the state of emergency lasts. But politicians are likely to pass many laws that will remain in place long after the end of the current crisis. Use of telecom data to track the whereabouts of mobile phone users is one example referring to privacy, the passing of laws criminalizing the spread of false information further endangers media freedom and the functioning of pluralistic democracy tout court. Third, some governments are likely to try to bypass parliament entirely by ruling by decree. The example of Viktor Orbán has already been mentioned.

If states of emergency are so often misused, why don’t we experience more opposition against calling them in the first place? In times of crises, the feeling that “something needs to be done” is a very human sentiment, but also a real problem called “action bias”. For many citizens, it therefore seems comforting to observe that their governments are “doing something”. Yet, the heat of the moment is usually a bad advisor. Therefore, states of emergency should only be allowed for a limited time clearly spelled out in legislation. Furthermore, any legislation passed under a state of emergency should automatically cease to be valid with the end of the emergency. To keep it, it should be subject to broad public discussion and pass the conventional parliamentary readings again. Both these insights were realized in the Roman Republic more than two millennia ago but appear to have been forgotten. Finally, the competences of some international organizations might need to be readjusted. Given all the evidence regarding the dangers of a state of emergency, it is difficult to comprehend how the World Health Organization could encourage countries to declare a state of emergency. If not, the separation of powers that has characterized the developed world since 1945 may be yet another victim of the crisis.

Helfen Sie, die Verfassung zu schützen!

Die Verfassung gerät immer mehr unter Druck. Um sie schützen zu können, brauchen wir Wissen. Dieses Wissen machen wir zugänglich. Open Access.

Wir veröffentlichen aktuelle Analysen und Kommentare. Wir stoßen Debatten an. Wir klären auf über Gefahren für die Verfassung und wie sie abgewehrt werden können. In Thüringen. Im Bund. In Europa. In der Welt.

Dafür brauchen wir Ihre Unterstützung!

[…] justified as an appropriate calibration of human rights and necessity. In the COVID-19 pandemic, around 100 countries from all continents of the world have declared states of emergency to expand governmental powers on all fronts, presumably to deal with all the uncertainties of this […]

[…] de todos los continentes han decretado estados de alarma o de emergencia, o figuras afines, en los términos establecidos en sus Constituciones y demás leyes formales, que los han habilitado para adoptar medidas […]