Veto Player and the Greek Constitution, Part 2

For part 1 of the series (introduction), click here.

2. A long constitution is a (positively) bad constitution[1].

Constitutions are “locked” documents because they are the stable basis of all legislation in a country. They require qualified majorities to be modified. The Greek constitution specifies that “two separate parliamentary votes on either side of a general election and a majority of three-fifths of the total number of seats in at least one of the votes” is required for all changes. This 29-word summary of Article 110 of the Greek constitution condenses the article from the original six paragraphs and uses 255 words! In other words, it is almost 10 times as long. We will return to this point in a while.

Constitutions can be “locked” in different ways: qualified majorities of a parliament may be required; agreement of multiple chambers may be required; referendums may impose additional requirements at the end of the process; and/or certain articles may not be amendable (usually human rights). We will examine the impact of these “locking” devices in a while, but for the time being, we could form an expectation, that the more locked a constitution, the more difficult it is to be modified, and the fewer amendments it will have over the years. This is an equilibrium statement, because what is the reason for locking a constitution, if not to prevent modifications, and if these locking devices work, we should not be seeing many amendments. In other words, the expectation should be a negative relationship between the existence of “locking” provisions and amendments.

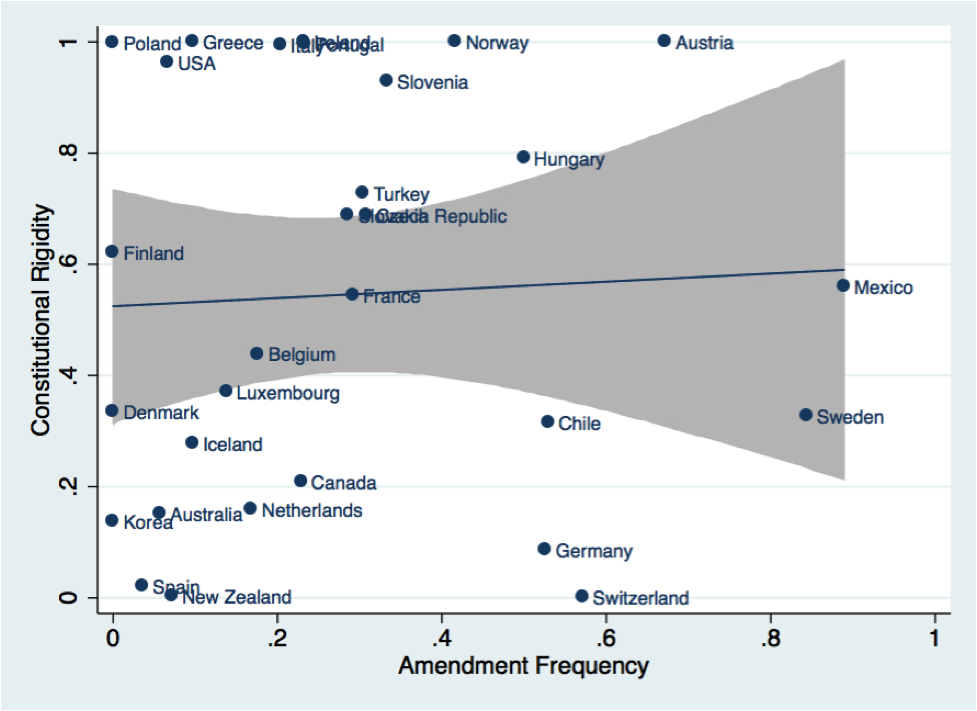

Figure 3, presents the actual relationship between locking (“rigidity”) and frequency of amendments in OECD countries. We selected these countries because chances are their constitutions will be documents respected and enforced, while in third world countries constitutions may not be either, and information about such documents would not reflect what is happening in the country. The data I am presenting here come from the Comparative Constitutions Project (Elkins et al., 2009) included in the Google dataset “Constitute”. The slope of this relationship between difficulty of modification and actual amendments not only is not negative (as we expected) but if anything it is positive. This is the first puzzle that we will explore.

Statistical analysis enables us to “control for” additional variables, that is, if we consider other variables that may affect both “locking” and frequency of amendments, we can take their impact out of the relationship and reexamine the graph. The expectation would, as before, is a negative slope; countries that have locked their constitution (controlling for any variable) should have fewer amendments (controlling for the same variable).

Locking and frequency of amendments, controlling for the length (logged) of the corresponding constitution

Figure 4, presents the same relationship of locking and frequency of amendments, controlling for the length (logged) of the corresponding constitution[2]. The relationship is even more pronounced and in the wrong direction. This is the second and more important puzzle we will try to explain. Here is what Figure 4 suggests: the longer a constitution the more “locked” it is, that is, the more difficult it is to be amended. Yet, the longer constitutions also undergo the most frequent revisions, and do so despite the fact that they are more locked. Why would the longer and more locked constitutions be the more inadequate (“bad” as the title of this section calls them)?

Let us start our investigation by trying to understand what “length” of a constitution reflects. It can reflect the number of topics included in a constitution, it can reflect the complexity of organization of the state (a federal government may require more articles of the constitution in order to regulate the interactions between the different levels of government, or it could delegate more decisions to states and their constitutions like the US constitution that delegates all the powers not enumerated in the document itself to the states), and it can reflect the details or restrictions imposed by the constitution on each subject. Generally, constitutions include more topics the more recent they are, so, a good proxy for the number of subjects included in a constitution is the age of the original document. A preliminary investigation indicates that the most relevant variable associated with constitutional length is the average number of words of devoted to each topic, that is, the number of “details” or “restrictions”.

Although we know that the length of a constitution is essentially an aggregate of the “detail” included in each of the covered issues, we do not know the reason, or content of this length. Constitutions can include three different kinds of provisions. First, constitutional provisions can regulate technical or innocuous matters that do not impact political behavior (such as descriptions of the national flag). Second, constitutions can contain aspirational goals, such as the right to work (included in many post World War II constitutions), which do not impose any specific obligations on the government, and consequently are not enforceable in court (not surprisingly, none of these countries has completely abolished unemployment). Third, constitutions contain restrictive or prescriptive statements. Most constitutions contain sections detailing government structure and the rights of citizens. For example, the U.S. president cannot circumvent the constitutional requirement that he seek the “advice and consent” of the Senate for presidential appointments. While these three categories of provisions maybe straightforward at the theoretical level, there is no direct way of distinguishing between constitutions that contain many substantive restrictions as opposed to those that are simply garrulous (Voigt, 2009). We will try to make inferences about the relative importance of each part.

Constitutions are typically amended after extraordinary procedures. These high hurdles of approval and modification guarantee that the constitution at the moment of adoption or modification is located in the “constitutional core” of a country. The “core” of a political system is a technical term referring to the set of points that cannot be upset by some specified majoritarian procedure. So, the “constitutional core” means the document that cannot be replaced by any other under the existing requirements for constitutional revision.

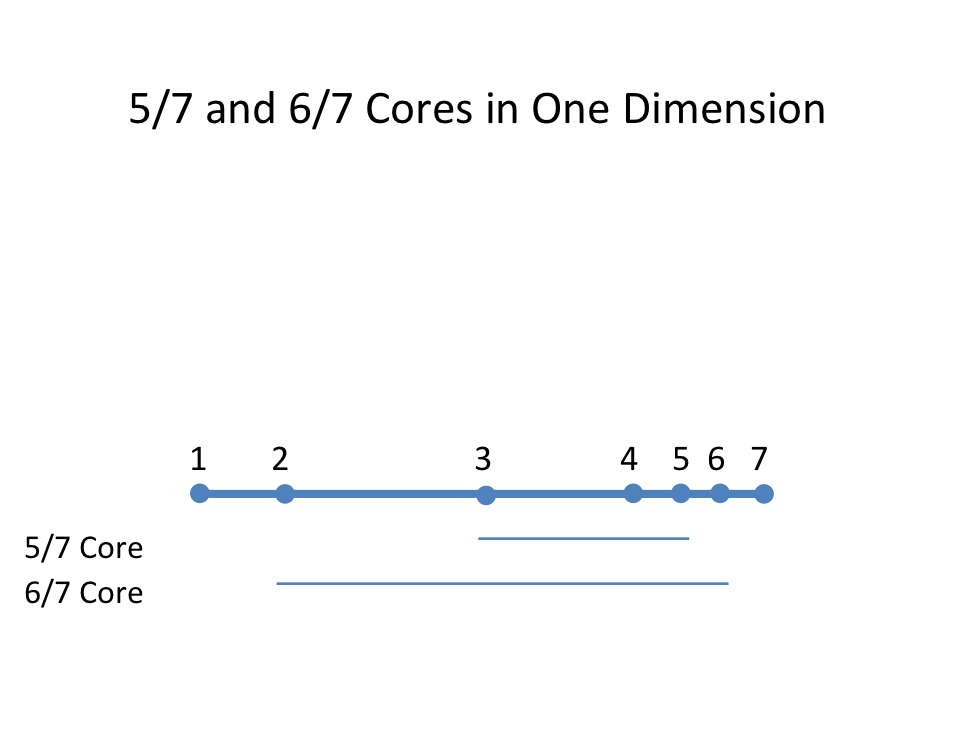

Let us consider a body that decides by qualified majority rule in one dimension (like a parliament with a single chamber[3]). In Figure 5, I present a seven-member body that decides by a qualified majority of 5/7 or 6/7. The reader can verify that when the qualified majority increases from 5 to 6 members, the core expands (from the 3-5 segment to the 2-6 segment).

Tsebelis and Nardi (forthcoming) argue that a constitution will be located inside the core of the political system. Indeed, any proposal outside the core would be defeated by a point inside the core. As for constitutional revisions, they argue that the only way they become an option is because a point that was inside this core is now located outside. In other words, a constitutional revision can involve only points (and provisions) that used to be centrally located inside the body politic of a country but ceased to occupy such a location, and the new core does not include them anymore.

This change can occur only under a significant modification of the positions of the individual players (or exogenous shocks that make the previous positions no longer tenable). Figure 5 presents such a modification in one dimension to make things clear. The underlying assumption is that a qualified majority in one only chamber is required for the revision.

In the example, out of the 7 members, 5 have shifted and moved (some of them significantly to the right). In particular, players 1 and 2 remained in place, while player 3 moved slightly to the right (from 3 to 3’), player 4 moved by a substantial amount (to position 4’ which is leapfrogging the old player 5), and players 5, 6, and 7 in their new positions (5’, 6’ and 7’) moved outside the whole political space of the past (beyond point 7 of the figure). This is a political change so radical that it is difficult to imagine in any real polity outside a revolution. Yet, the 5/7 core was only slightly modified: player 3 has moved outside the core and player 7 is now within the core. More to the point, it is only if the constitution involved a provision in the (3,3’) area that there are grounds for a constitutional revision if the required constitutional revision majority is 5/7. On the other hand, if the required majority for constitutional revision is 6/7, then there is no possibility for such a modification (despite the significant shift of the public opinion). Then voter 2 will preserve the constitution by voting down the amendment. From the above discussion follows that a constitutional change requires a point of the previous constitutional core (an article or a section of the existing constitution) to be located outside the current constitutional core of the polity.

On the basis of the above analysis, given the large size and the central location of these constitutional cores, it is very likely that the two cores (at time t and t+1) will overlap. Points in the intersection of the two cores cannot be subject of constitutional revisions (by the definition of “core”). The only provisions that could be changed are the ones that belong in the core at time t but not in the core at time t+1,as illustrated in with player 3 in Figure 6. Unlike simple legislation that (usually) requires a simple majority in parliament, and can be changed by a different majority (left succeeding right or vice versa), the required constitutional majorities include parts of the previous majorities. Consequently, constitutional revision requires a massive change in the opinions of the political actors.

What are the implications of this analysis? Constitutional revisions can occur either because the preferences of political forces changed (in other words, they recognize that they had made a mistake in the original draft) or because external conditions changed significantly such that new provisions are considered necessary (for example, an economic crisis). But why should all these difficulties of locking and unlocking be associated with long constitutions? Figure 4. above provides the answer that length is not an innocuous variable associated just with the number of words. It is a summary indicator of the level of restrictive provisions associated with each item included in the constitution. And it is these restrictions that enter into conflict with an evolving reality which generate the need for change (despite the difficulties of unlocking the constitution).

The focus of constitutional revisions is on prescriptive or proscriptive provisions, not on hortatory or aspirational statements. The very attempt to amend the constitution indicates that the existing constitution had (in the opinion of overwhelming majorities in the country) serious shortcomings, and these shortcomings were experienced and understood as such. This is a fundamental point of the analysis. The frequency of revisions indicates that the constitutions are not just garrulous, but also impose objective, negative costs on society. Tsebelis and Nardi (forthcoming) connect lengthy constitutions with low GDP per capita, and corruption. Here I will present only the last Table of their findings:

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Detail | -0.827** | -0.849** | -0.785* | -0.832** |

| (0.29) | (0.27) | (0.29) | (0.27) | |

| # Amendments Under Democracy | 0.006** | 0.005** | 0.007** | 0.006** |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Education (% in labor force) | 0.00 | -0.001 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Natural Resources (% GPD) | -0.009 | -0.014* | -0.01 | -0.015** |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.01) | (0.01) | |

| Trade Openness (% GDP) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Investment (% GDP) | 0.010** | 0.010** | ||

| (0.00) | 0.00 | |||

| Savings (% GDP) | 0.009* | 0.008* | ||

| (0.00) | (0.00) | |||

| Corruption (TI) | -0.043*** | -0.039*** | ||

| (0.01) | (0.01) | |||

| R^2 | 0.7786 | 0.7784 | 0.7725 | 0.7626 |

| N | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001 |

Table 1: GDP per capita Regressed on Constitutional Restrictions (detail) and Corruption

According to Table 1 the variable “detail” has a big negative impact on GDP per capita despite most of the controls of economic literature (education, natural resources, trade openness, investment, savings) as well as corruption. But our analysis about constitutional rigidity and amendments indicates that “detail” is de fact an indicator for restrictions.

In conclusion, long constitutions are bad constitutions because they are too restrictive (as indicated by the length of their provisions). They impose burdens on the countries that they are supposed to regulate. These populations succeed frequently in modifying the constitutions (we have no measure of how many times they tried and failed because of the effectiveness of the restrictions included in the constitution itself. This is a subject that we will develop in the next section.

[1] This part is a summary of Tsebelis, George and Dominic Nardi, Jr. “A Long Constitution is a (Positively) Bad Constitution: Evidence from OECD Countries” forthcoming British Journal of Political Science. For a detailed analysis see the original

continue to part 2: Barking up the wrong tree

[2] We log (use the logarithm instead of the natural number) because the effect of length is not constant over time: the first 1000 words of a constitution are more significant than the tenth.

[3] The interested reader can consult Yataganas, X., & Tsebelis, G. 2005. The treaty of Nice, the convention draft and the constitution for Europe under a veto players analysis. European Constitutional Law Review, 1(3), 429-51, in order to see what the core of multiple chambers in two dimensions looks like. It is sufficient here to argue that it “expands” as the number of chambers and the qualified majorities in each one of them increases.

Helfen Sie, die Verfassung zu schützen!

Die Verfassung gerät immer mehr unter Druck. Um sie schützen zu können, brauchen wir Wissen. Dieses Wissen machen wir zugänglich. Open Access.

Wir veröffentlichen aktuelle Analysen und Kommentare. Wir stoßen Debatten an. Wir klären auf über Gefahren für die Verfassung und wie sie abgewehrt werden können. In Thüringen. Im Bund. In Europa. In der Welt.

Dafür brauchen wir Ihre Unterstützung!